Considered the father of modern computing and voted ‘The Greatest Person of the 20th Century’ earlier this year, Alan Turing has today been afforded the further honour of being announced as the new face of the Bank of England’s £50 note.

What many don’t realise is the depth of Turing’s connections to Altrincham.

Here Jonathan Swinton, author of a new book on Turing’s years in Manchester, explains all.

ALTRINCHAM TODAY: What first got you interested in Alan Turing?

JONATHAN SWINTON: Thirty five years ago when I was a maths student, a new biography of Alan Turing came out. At the time almost no one had heard of him, and I wasn’t particularly interested in the bits everyone else was interested in about codebreaking, or even his tragic death.

I was interested in the work he was doing on where flowers get their shapes from… so it was rather a niche interest. And then when I came to Manchester 15 years ago I was surprised that I found myself living in the same suburb as Turing had done 60 years earlier. It was putting the two things together that started my book off.

AT: What’s the connection between Turing and Altrincham?

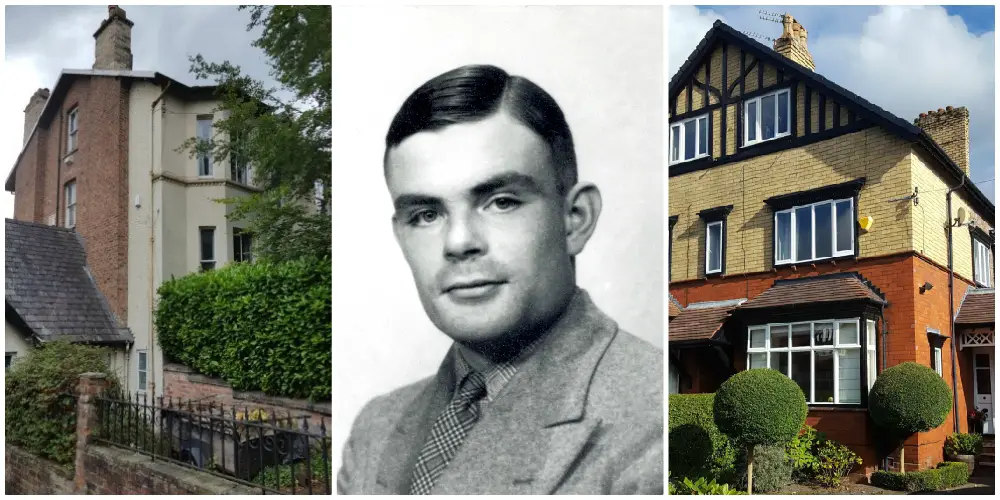

JS: The most direct connection is that Turing lived on Nursery Avenue in Hale for a couple of years when he first came to Manchester in the late 1940s. He wasn’t hugely impressed; he thought Manchester was dirty and the young men not that attractive, and he was too scared of his landlady to ask for extra coal for the fire, so he had a bit of a shivery time. But it wasn’t so bad; his boyfriend from Cambridge would visit, and he had an amazing new job.

AT: What did Turing do in Manchester?

JS: Turing came to be the programming expert on the new Manchester Mark I, the computer that the engineers Freddie Williams and Tom Kilburn are famous for building, and which in some ways could be called the first computer in the world. People sometimes argue about where the credit should go, though there’s plenty to go round.

Although Turing had in a way come up with the idea of the computer well before the war, it was the codebreaking equipment at Bletchley Park that really showed people the next steps, but Williams and Kilburn didn’t know about Bletchley, only what Turing and Turing’s boss Max Newman could tell them. Actually it was Newman who got all the money to start the project off. In an important way Turing and Max Newman have credit for the Mark I alongside Williams and Kilburn, even though the two mathematicians had nothing to do with the brilliance of the engineering design.

When Turing actually got his own time on the computer what he chose to work on was that problem of flower growth, where Fibonacci numbers came from, that I had been interested in all those years ago. We did a project with the Museum of Science and Industry a few years ago about these patterns in sunflowers, and I was struck by how many people were interested in Turing’s time in Manchester. Hence the book.

AT: Where did the others live?

Kilburn was a Yorkshire lad and at first commuted to the University from his parents in Dewsbury to save money, but he ended up in Urmston. When Williams made some money as a Professor he bought a great big house on Park Road in Timperley. But Bowdon was where Max Newman chose to live, in a house on Vicarage Lane. He wasn’t the only University Professor; there was a brilliant chemist and average philosopher named Michael Polanyi who lived on Gilbert Road in Hale. The Newmans and Polanyis were Turing’s family in a way – he would be invited round for dinner and end up sitting on the ground playing with the children. He would often run miles to their houses without carrying any money or a bag; once he turned up too early in the morning to knock on the door but left a message scratched onto a laurel leaf with a stick.

AT: What happened on Vicarage Lane?

JS: We know what Newman and Turing were planning: it was to create machines that could think, and not everybody thinks this is a good idea. They don’t leave much record of how they felt about it. Fortunately Max’s wife Lyn had been a literary journalist before the war – she knew Virginia Woolf for example – and she’s left some vivid accounts of listening to these men chatting. She didn’t mind them making machines to add up quickly, though she was a bit mystified obviously clever men were interested in something so boring. But when she heard them talk about how they might make a machine too complicated for any human to understand she started to feel a bit queasy. Part of today’s worries about, say, Facebook, go back to that back garden conversation in the Newmans’ house.

AT: Do you think Turing liked Manchester?

JS: After a couple of years, Turing was earning enough to buy a house and moved to Wilmslow, perhaps to avoid that landlady. But he always kept in touch with the Newmans and Polanyis, and later with the family of his therapist in Didsbury. When Turing was prosecuted for gross indecency in 1952, it was Max Newman who stood up in court and said ‘Alan Turing is my friend’. So some of the people were very important to him. Turing was particularly close to Lyn Newman, but she ended up leaving Manchester, and more-or-less leaving Max, because she couldn’t bear how dirty and unliterary the city was. Max lived in a few other places around Bowdon, including what is now the Mercure on Marlborough Road, just opposite to where, 30 years later, the Smiths wrote Meat Is Murder…

Alan Turing’s Manchester, by Jonathan Swinton, is available at Abacus Books, Idaho, California Coffee and Wine and Waterstones Altrincham. He blogs at manturing.net/manufacturing where the book can be ordered online.